How the art for KING FOR A DAY came to be

This interview was conducted by author Rukhsana Khan

RK: How did you get the inspiration for the illustrations?

CK: At the very beginning, when I had read the manuscript but was still waiting for the finished version I visited an exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art called Wonder of the Age: Master Painters of India 1100-1900. I came out transformed, almost as if I was on LSD. I felt such a burst of color inside of me, such artistic possibility, such a surge of energy. Next I found out that Lahore, where your story takes place, was a major city of the Mughals! That’s when I knew: This is it! I have to do the whole book in Mughal miniature style!

At that time, I still knew very little about Pakistan. I once had a fantastic Pakistani roommate but realized with regret that I’ve asked her way too few questions about her whereabouts. I knew about Pakistan and India being separated, I’d seen my fill of Bollywood movies about that subject, but I didn’t know a lot about the actual geography. Before I was offered to illustrate your story I didn’t know that Lahore even existed. And I didn’t know that culturally India and Pakistan were so close.

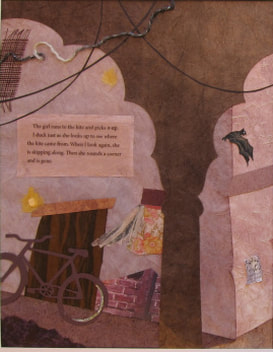

But the more research I did, the more I felt that I virtually lived in Lahore. When I really started to catch fire was when I found out about the existence of the beautiful old city of Lahore, the Walled City. There were narrow alleys that were literally woven together with electrical wires, there were goats, bicycles, skinny cats, hairdressers discussing politics on the doorsteps, children playing, cracks in the walls of ancient Mughal facades, walls that were covered with flyers in beautiful Urdu calligraphy… I could only imagine the smells and sounds of it… and I began to make my virtual home there. Now I knew exactly where the kids in the book should live!

This interview was conducted by author Rukhsana Khan

RK: How did you get the inspiration for the illustrations?

CK: At the very beginning, when I had read the manuscript but was still waiting for the finished version I visited an exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art called Wonder of the Age: Master Painters of India 1100-1900. I came out transformed, almost as if I was on LSD. I felt such a burst of color inside of me, such artistic possibility, such a surge of energy. Next I found out that Lahore, where your story takes place, was a major city of the Mughals! That’s when I knew: This is it! I have to do the whole book in Mughal miniature style!

At that time, I still knew very little about Pakistan. I once had a fantastic Pakistani roommate but realized with regret that I’ve asked her way too few questions about her whereabouts. I knew about Pakistan and India being separated, I’d seen my fill of Bollywood movies about that subject, but I didn’t know a lot about the actual geography. Before I was offered to illustrate your story I didn’t know that Lahore even existed. And I didn’t know that culturally India and Pakistan were so close.

But the more research I did, the more I felt that I virtually lived in Lahore. When I really started to catch fire was when I found out about the existence of the beautiful old city of Lahore, the Walled City. There were narrow alleys that were literally woven together with electrical wires, there were goats, bicycles, skinny cats, hairdressers discussing politics on the doorsteps, children playing, cracks in the walls of ancient Mughal facades, walls that were covered with flyers in beautiful Urdu calligraphy… I could only imagine the smells and sounds of it… and I began to make my virtual home there. Now I knew exactly where the kids in the book should live!

Eventually, I even downloaded maps of the Walled City and decided where our kids’ roof would have to be so they’d have a good view of Badshahi Mosque, the beautiful Mughal style landmark of Lahore that resembles the Taj Mahal. Without ever having physically been there, I became a little bit of a “virtual patriot”.

RK: How did you start designing the book?

CK: My very first impression, prior to the Mughal exhibit, hadn’t been very good. I had done research on youtube and I was really put off, because what I found when I typed in “basant” were only grainy amateur videos of macho men on roofs. No woman in sight! Full of cynicism I thought, ‘That’s not a national holiday, it’s a men’s holiday.’ At the same time I knew that when a project comes to me, it comes from a higher source. It is an offer to make visible deep humanness, its an offer to go on an intense, work-filled joyride. And so I just knew that I’m going to transform it into something beautiful.

Finally I got the manuscript I could work with. I did pencil sketches, and the publisher and I discussed many changes before I could, at last, rummage through my boxes full of colorful papers for the actual artwork. I ended up not working in the Mughal miniature style but in my old collage style that I had developed in my previous books. However, I made sure that, like in the miniature paintings, the Mughal style arches of Lahore are like a red thread that leads through the whole book, beginning with the title and even the dedication-page. And on one page, I drew many little children who are catching kites on a tan-colored Indian paper, just like the Mughal miniatures.

Today’s cityscape of Lahore seems to be pretty beige, but since the story takes place during a joyous festivity, I wanted there to be a feast of color on every page, not just the culmination page where all the kites are in the sky. Suddenly I got a great idea: I went out and bought fabric swatches with gorgeous textures and patterns in the Indian and Pakistani fabric stores around 39th Street in Manhattan.

RK: How did you start designing the book?

CK: My very first impression, prior to the Mughal exhibit, hadn’t been very good. I had done research on youtube and I was really put off, because what I found when I typed in “basant” were only grainy amateur videos of macho men on roofs. No woman in sight! Full of cynicism I thought, ‘That’s not a national holiday, it’s a men’s holiday.’ At the same time I knew that when a project comes to me, it comes from a higher source. It is an offer to make visible deep humanness, its an offer to go on an intense, work-filled joyride. And so I just knew that I’m going to transform it into something beautiful.

Finally I got the manuscript I could work with. I did pencil sketches, and the publisher and I discussed many changes before I could, at last, rummage through my boxes full of colorful papers for the actual artwork. I ended up not working in the Mughal miniature style but in my old collage style that I had developed in my previous books. However, I made sure that, like in the miniature paintings, the Mughal style arches of Lahore are like a red thread that leads through the whole book, beginning with the title and even the dedication-page. And on one page, I drew many little children who are catching kites on a tan-colored Indian paper, just like the Mughal miniatures.

Today’s cityscape of Lahore seems to be pretty beige, but since the story takes place during a joyous festivity, I wanted there to be a feast of color on every page, not just the culmination page where all the kites are in the sky. Suddenly I got a great idea: I went out and bought fabric swatches with gorgeous textures and patterns in the Indian and Pakistani fabric stores around 39th Street in Manhattan.

Now the real ecstasy began. My workspace turned into a colorful landscape of papers, fabrics, photos of Pakistani street scenes, cutout shapes of children I had drawn, inkpots, brushes, pencils… and my ever-present teapot. No wall, no surface was there that didn’t have anything Pakistani or silken or satin on it. In the middle was always my illustration board on which it would all assemble. There, tiny bits of paper pieces would be endlessly pushed around until they found their perfect spot. I’m sorry to say that this is all that got published, and not the colorful mess around it as well!

For me though, an illustration stands or falls with whether the faces of the people on it are beautiful. If they are not I’m not satisfied with the whole page, no matter how gorgeous the colors. The faces can be the hardest part, and the hardest to control. They seem to have a life of their own; they have true personalities, and it is up to them if they want to appear at my pencil’s tip or not. Sometimes they simply seem to fall on the paper by themselves and look great right away, and on other days I can draw the same face over and over a hundred times, and each time again it looks like a grimace. That is illustrator hell!

When I worked on Anh’s Anger I had very little time. So without doing any pencil sketches, I jumped right into the finals. That’s where the book got its slammed-together, lively look. But King for a Day became a very detailed work because it was based on very detailed pencil sketches. It was meticulously planned.

RK: So did you really grow from this process?

CK: I did.

RK: In what ways did you grow?

CK: I grew a lot in communicating with the editor and art director. I’ve never been as authentic in my professional communication, talking about what is going on in me internally during the artistic process. And when we were discussing changes I was really speaking from the heart. I learned to trust that if I do that, good things will happen. All that good stuff will go into the book, and you can feel it when you hold it in your hands. I live in New York, and since 9/11 and then Hurricane Sandy (during which I worked on this book), my perception of life completely changed: I realized that life can be over at any minute, so you have to do what is important in your life NOW, or it might be too late. Every book could be my last. So it has to become good! I have to risk everything - making myself vulnerable, being true to myself, fighting for my ideas. And I know that insisting on my vision of how I want the illustrations to look is not an expression of my egotistic willfulness, but it means to fully accept my responsibility for them. It means to enable this beautiful vision I see “somewhere up there” to really come through me and turn into reality, radiate out into the world as a gift to everyone. If I don’t stand up for my vision it feels as if life would have been in vain. It’s just that intense.

At the very beginning when I did research about Pakistan, before I had discovered Mughal miniature painting and the beauty of the Walled City of Lahore, I had found many disconcerting things. Apart from the macho men on the roofs, I came across a lot of images of violence. But even then I knew, love, vitality and plain human goodness just have to be there somewhere. There is no way it cannot be. I just had to find it, trust that it is there, connect to it, and if it all starts in my own heart. So I was trying to find a sacred space within myself from which I could work, out of which I could create beauty. And then, there it was: In my inner landscape appeared a market place inside of a tall Mughal style building. Rays of light from high-up windows fell silently upon everything. It was a casual, every-day place, not a mosque, not a religious place, and yet it felt sacred, because I realized, only good people, or the highest part of people could go there. Everyone moved in peacefulness and calm. There were young people, old people, women, men, children, donkeys, pigeons, sacks of grain and straw. There were wonderful, yet every-day smells: the scent of burned wood, rosewater, donkey dung. And this turned into the first illustration I did.

There was no mention in the manuscript about this market scene, but it felt so natural to include it. Half way done, I suddenly expected that the editor would want me to take it out, but it seemed to work well.

For me though, an illustration stands or falls with whether the faces of the people on it are beautiful. If they are not I’m not satisfied with the whole page, no matter how gorgeous the colors. The faces can be the hardest part, and the hardest to control. They seem to have a life of their own; they have true personalities, and it is up to them if they want to appear at my pencil’s tip or not. Sometimes they simply seem to fall on the paper by themselves and look great right away, and on other days I can draw the same face over and over a hundred times, and each time again it looks like a grimace. That is illustrator hell!

When I worked on Anh’s Anger I had very little time. So without doing any pencil sketches, I jumped right into the finals. That’s where the book got its slammed-together, lively look. But King for a Day became a very detailed work because it was based on very detailed pencil sketches. It was meticulously planned.

RK: So did you really grow from this process?

CK: I did.

RK: In what ways did you grow?

CK: I grew a lot in communicating with the editor and art director. I’ve never been as authentic in my professional communication, talking about what is going on in me internally during the artistic process. And when we were discussing changes I was really speaking from the heart. I learned to trust that if I do that, good things will happen. All that good stuff will go into the book, and you can feel it when you hold it in your hands. I live in New York, and since 9/11 and then Hurricane Sandy (during which I worked on this book), my perception of life completely changed: I realized that life can be over at any minute, so you have to do what is important in your life NOW, or it might be too late. Every book could be my last. So it has to become good! I have to risk everything - making myself vulnerable, being true to myself, fighting for my ideas. And I know that insisting on my vision of how I want the illustrations to look is not an expression of my egotistic willfulness, but it means to fully accept my responsibility for them. It means to enable this beautiful vision I see “somewhere up there” to really come through me and turn into reality, radiate out into the world as a gift to everyone. If I don’t stand up for my vision it feels as if life would have been in vain. It’s just that intense.

At the very beginning when I did research about Pakistan, before I had discovered Mughal miniature painting and the beauty of the Walled City of Lahore, I had found many disconcerting things. Apart from the macho men on the roofs, I came across a lot of images of violence. But even then I knew, love, vitality and plain human goodness just have to be there somewhere. There is no way it cannot be. I just had to find it, trust that it is there, connect to it, and if it all starts in my own heart. So I was trying to find a sacred space within myself from which I could work, out of which I could create beauty. And then, there it was: In my inner landscape appeared a market place inside of a tall Mughal style building. Rays of light from high-up windows fell silently upon everything. It was a casual, every-day place, not a mosque, not a religious place, and yet it felt sacred, because I realized, only good people, or the highest part of people could go there. Everyone moved in peacefulness and calm. There were young people, old people, women, men, children, donkeys, pigeons, sacks of grain and straw. There were wonderful, yet every-day smells: the scent of burned wood, rosewater, donkey dung. And this turned into the first illustration I did.

There was no mention in the manuscript about this market scene, but it felt so natural to include it. Half way done, I suddenly expected that the editor would want me to take it out, but it seemed to work well.

In a previous version of the back matter you not only wrote about the food and the festivities around basant, but that you were standing on the roof and eating an orange, so I included a lot of oranges in the illustrations, and I could just imagine the smell of orange blossoms all over Lahore!

That’s why there’s also an orange vendor.

RK: Oh that’s hilarious! No wonder there’s such a tinge of orange through the illustrations! I loved that first illustration. You start on the ground and get to the roof! You’re going up!

RK: How many books have you illustrated?

CK: This is my sixth book.

RK: Can you name the other books?

CK: The very first book I did was a West African tale called The Treehouse Children, published by Simon & Schuster in 1994

Then came Flower Girl Butterflies, published by Harper Collins.

The third book was for a Japanese religion called Tenrikyo and was published by Tenri Cultural Institute. The book’s title is God the Parent’s Blessings.

RK: So did you get to go to Japan?

CK: Three times, and the third time they invited me in appreciation of the art I did for the book.

Then, the fourth book was Anh’s Anger, published by Plum Blossom Press, the children’s book imprint of Parallax Press. This is the Buddhist publisher that publishes the books of Vietnamese Zen teacher Thich Nhat Hanh. Anh’s Anger is a story that follows his teachings.

The fifth book was Steps and Stones, the second book in the Anh’s Anger series, in which the boy Anh goes on walking meditation with his “friend”, the Anger.

And now, there is King for a Day. It has been a work of two years.

RK: Well I think you’ve done a fabulous job on King for a Day! And it’s been such a pleasure getting to know you Christiane and know more about your creative process!

CK: And thank you, Rukhsana, for writing such a wonderful story! Because of it, my vision of the world has expanded. And without it, I would have never known about the oranges in Lahore!

RK: Well I think you’ve done a fabulous job on King for a Day! And it’s been such a pleasure getting to know you Christiane and know more about your creative process!

CK: And thank you, Rukhsana, for writing such a wonderful story! Because of it, my vision of the world has expanded. And without it, I would have never known about the oranges in Lahore!